The Nation State and the Promised Land: An American Yiddish Writer in Israel, 1949, by Solomon Simon. English translation, 2024, by David R. Forman. All rights reserved.

Page numbers from Medines Yisroel un Erets Yisroel, 1950, Farlag Matones (NY), are included for those who wish to follow along with the original Yiddish, below.

To begin with the Introduction, click here.

I returned from Jerusalem, arriving in Tel-Aviv at two o’clock in the afternoon on the day of the military parade. I then went to take a bus to Ra’anana. The bus, which was always packed and would leave passengers behind because it couldn’t take them all, was completely empty. Only one old woman sat on the back bench. The driver, who already knew me well, because I had often rode to Ra’anana with him, looked at me astonished.

“You’re leaving from Tel Aviv now? People are coming from every corner of the country to watch our military parade and you’re going back to Ra’anana two hours before the parade starts?”

I answered him curtly:

“I don’t like military parades.”

The bus left the station. The bus driver turned his steering wheel and talked to me:

“You are a strange American tourist. All your tourists run to see our greatness and strength and you come out with, ‘I don’t like military parades.’ You are forgetting one thing, good sir: This is a Jewish military parade. Once our parades consisted of binoreynu uviskeyneynu, young and old, going out to welcome a Lord with bread and salt and a Torah scroll. The

p.76

goy was in the know and understood the obvious hint: In the Torah it says “Do Not Murder.” The goy looked at us with revulsion—little Jews, weaklings, cowards, trembling at a little blood. Now we are going to show them that we know war, too. Let them develop some respect for us.”

The old woman dozed in the back of the bus. I sat near the driver and answered him:

“My father used to say, a Jew can do anything a goy can do and more. Brilliant — killing people! But to learn a bit of Chumesh with Rashi’s commentary, that the goyim can’t do. I am still an old-fashioned Jew who believes that “Loy bekheyl veloy bekoyekh…” Not by arms and not by power, but by my spirit, said the Lord of hosts.

And he answered me angrily:

“What do you have to do with scripture verses? You don’t dress or conduct yourself like a religious Jew; let the rabbis break their heads interpreting verses. I think enough of us have died with verses in their mouths. Better to live with a gun in your hand.”

“I hate Yevonim,[1]” I answered defiantly. “A yoven is a uniformed murderer. It is not fitting for Jews to boast about soldiers!”

He stopped the bus out of anger. The old woman woke up from the jostling. “What happened?” she asked, alarmed.

He set off again and began talking. Truly distressed, he poured out his bitter heart to me:

“For weeks now I’ve driven you back and forth, from Ra’anana to Tel-Aviv and from Tel-Aviv to Ra’anana, and I’ve heard enough of your speeches. You rarely stick to the subject. You are always chastising us and tormenting us. For sins of commission and sins of omission. Today you’re just talking nonsense. It could be that goyishe soldiers are uniformed murderers, but our soldiers saved the Yishuv! What do you think; we could have fought the English and the Arabs with bible quotations? And your United Nations in Lake Success, and your precious America? They understand one language — the fist! We…

p.77

punched back and we are going to keep punching. Blessed be the hand that aims and hits its mark! Uniformed murderers…” He spat out the words between his teeth. “It’s not right to talk like that. A Jewish soldier here in our land is a hero!”

I sighed. “What can I do. I still hate soldiers. I see no beauty in military parades and I can’t stand them. OK, so it can’t be helped. If people have to fight, they fight. There’s no choice. It’s not a novelty for Jews to stand up against our enemies. In the diaspora we also fought wen we had to. One example is Tulchin. But to brag about guns and soldiers and make parades with them? This is not Jewish.”

“Nothing can be done with you,” he gestured dismissively. “You are a Jew of the Exile, an abject slave.”

I did not leave him wanting for an answer:

“You are from the diaspora yourself. Based on your Yiddish dialect, you are Ukranian. Nevertheless, you talk like a saved Jew, like a third generation Israeli!”

He was driving in a hurry and spoke without looking in my direction:

“I only know one thing. If we had followed Jews like you, we would not have been able to build the country, and absolutely not been able to win it. We would have been killed off by the Arabs. I have been an oytobus-nehag (driver) for fourteen years and until this last year, when I left for work in the morning, I have never been sure that I would come back home alive at night. Before, when I left my wife and my children every day, we would part in silence. What use is all this philosophizing to me? We will build our country. If we are permitted to build it in peace, so much the better. If not, we’ll use force. We will not go like lambs to the slaughter; enough of being killed like sheep and enough wailing and lamenting in prayer to the Master of the Universe afterwards. And I am telling you: We will not only defend ourselves, we will be the attackers —but only to prevent calamity.”

Apparently he was waiting for me to answer, but I remained silent. He spoke again:

p. 78

“For me, it’s no privilege to be an ato bekhartonunik[2], chosen by God to be slaughtered. To my way of thinking, if we parade with tanks, airplanes, artillery, the whole kit ‘n caboodle, then they’ll see it and be afraid.”

When I still did not answer him he spoke again, irritated:

“We are not just doing this for ourselves, but for all the Jews, even for you, so that you will have somewhere to come in time of need. You are fooling yourself. Calamity will come to you, too, in America. I’m telling you, exile has its logic.”

We rode the remaining part of the trip in silence. But interestingly, when he left me off in Ra’anana, he gave me his hand, smiled, and said:

“Don’t take offense at my sharp and angry words. You are a precious Jew, only you do not have the spirit of a normal citizen of a normal nation. You have the irrationality of a Goles-Yid[3].

I pressed his hand and answered:

“To me, the State of Israel is still Yidn-Land, the Land of Israel, and one may register complaints against Yidn-Land. When I reach the point that I have no complaints with you, that will not be good. Then we will have become divided too far.”

“That’s true,” he said. “A Jew must always strive for perfection. There must always be Jews who have demands and complaints. We sometimes get angry but don’t take it to heart. We get angry because we, too, do not want to stop being Jews. You think we always agree among ourselves? Peace.”

He drove off.

**

*

A week later, all the newspapers issued a call for the public to come to a Bialik[4] memorial, to be held at Bialik House on the anniversary of his death. The memorial would be conducted with the participation of the big shots of Hebrew Literature, among them Yakov Fichman, Asher Barash, and Isaac Dov Berkowitz.

My wife, my daughter and I came on time, at five o’clock…

p. 79

in the afternoon. We waited a half hour until the door of the house was opened. By half-past six there were forty people in the hall. The memorial began. At seven o’clock, I counted fifty-two people, over half of whom were American tourists. Yes, [Zalman] Shazar, the education minister, did come at the very end. All in all there were fifty-three people, including my thirteen-year-old daughter and two other children.

It was a tedious program, and not at all successful. A young writer read a long, drawn-out appraisal of Bialik. The talk lasted over an hour and the writer dwelled on every cliché that had ever been said of Bialik. Then, Yakov Fichman read a Bialik poem. He read very quietly, so you could barely catch the words. Finally, Asher Barash read some long and deeply patriotic essay he had found among Bialik’s writings. The essay was not at all characteristic of Bialik. After the memorial a few people walked to Bialik’s grave, which was not far from Bialik House.

I rode back to Ra’anana with my familiar bus driver. He greeted me:

“So, were you at Bialik’s memorial?”

“How did you know?”

“I figured,” he smiled, “that a man like you would not miss Bialik’s yortsayt. There probably wasn’t much of a crowd.”

“Well, you guessed it, but you were not there,” I wondered, “so how could you tell that only a few people went?”

“I know our people,” he said, distressed. “Look, when it comes to this, you can be angry and have a justified complaint against us. You can write harshly about it.”

“How did you know I will be writing about this?” I asked.

“A writer who visits the Land of Israel writes a book. Of course you will write a book. And you will probably criticize us more than enough. Today’s criticism will be justified. It’s really not good and not right for a military…

p. 80

…parade to captivate the entire community and for Bialik’s memorial to draw only a few dozen. Give it to us good, but without mercy! We ought to blush.”

“I probably will, for your sake,” I answered playfully.

When I got back to New York, I read a letter about Bialik’s memorial in a Hebrew newspaper. The writer described how wonderfully the memorial was conducted. The hall was packed and the crowd was spellbound. It was not a total lie. The little hall could not hold more than fifty people. It was not his responsibility to mention that the balcony was empty. And the program is, after all, a matter of taste.

(click here to continue reading Chapter 8)

[1] Yoven [pl. Yevonim]. In this context, yevonim derives from a usage that means ‘Russian soldiers,’ ‘Russian or Ukranian policemen’, but also ‘thugs’. See my comment, here.

[2] A Jewish chauvanist (here, ironic), imported into Yiddish from the Hebrew, “You have chosen us”.

[3] Goles can mean either ‘diaspora’ or, more commonly, ‘exile’. Among Zionists, the term Goles-Yid, or diaspora Jew, was not a compliment.

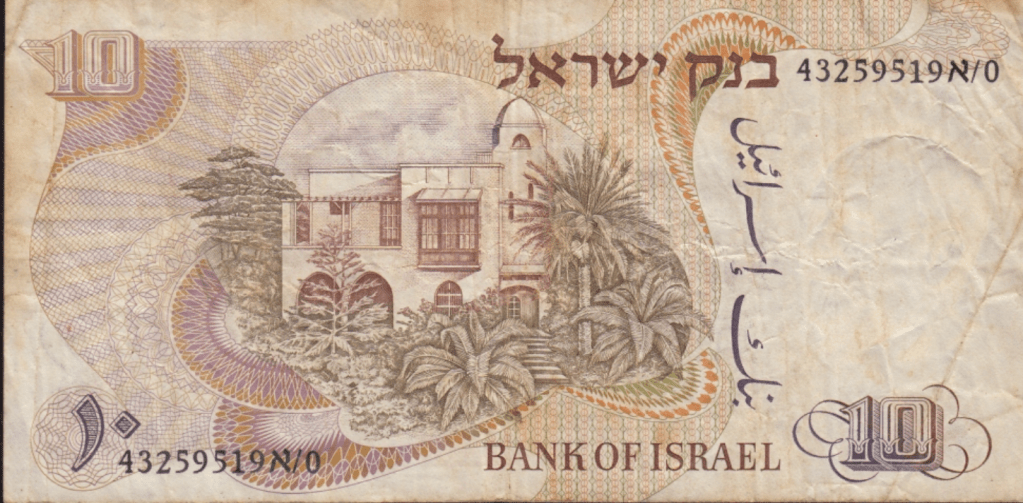

[4] Chaim Nachman Bialik (1873 – 1934), a poet who wrote mostly in Hebrew, but also in Yiddish, recognized as Israel’s national poet. The image accompanying this chapter is a 10 Lira note with a picture of Bialik House.