The Nation State and the Promised Land: An American Yiddish Writer in Israel, 1949, by Solomon Simon. English translation, 2024, by David R. Forman. All rights reserved.

Page numbers from Medines Yisroel un Erets Yisroel, 1950, Farlag Matones (NY), are included for those who wish to follow along with the original Yiddish, below.

To begin with the Introduction, click here.

I drew up a list of kibbutzim to visit. But before I set out, I did not want to overlook what was happening around Ra’anana. I did not want to be like those tourists who come to America, rent a room in New York, and then set out across the country without ever seeing New York.

Every nook and every village in Yidn-Land has its own flavor. It’s very different than in America, where you have to travel many miles in order to see some variation in Jewish life. In Israel there will be something remarkable, built on a completely different foundation, a fifteen-minute walk from you.

Jewish life in America is stable, more or less cast from one mold. In the State of Israel it is different. Even before it became the State of Israel, the Yishuv had taken upon itself to remake the Jewish people. A new principle was established: The individual must not only take care of his own spiritual and material happiness, but his fate must be woven into the fate of the community. The people stands in the center of the individual’s life and he, the individual, must organize his personal life according to the demands of the people.

One could say that this agrees with the direction of modern times. The tendency of the last decades is to place the nation, the state, in the center of individual life. Still there is a great difference between Israel and other countries.

p. 102

In the last three and a half decades, the Jewish People has suffered frightfully. The apex of the suffering came during the time of Hitler, may his name be blotted out. The damage that was done to the Jewish body and the Jewish soul was monstrously large. The State of Israel has taken it upon itself to repair the damage on a national scale. Such an undertaking requires a more ethical approach to the individual than in established countries. Other well-established countries can afford to ignore the individual, in order for the nation to get back on its feet. But the State of Israel must first rehabilitate the individual, in order for the state to establish itself.

And because the people is in the process of recreating itself, it requires a lot of freedom for the individual to have the choice of how to adapt himself. Therefore, wherever you look and wherever you turn, you see something different, something new, which surprises and astonishes you.

On a stretch of territory near Ra’anana, smaller than from Flatbush to Williamsburg, you can find: Kibutzim, workers cooperatives (moshavs), individual farms, hakhshore [preparatory, or technical training] kibbutzim, and children’s villages. You can get to many of them on foot. Before setting out for more distant trips, I visited these places near Ra’anana.

I took a walk over to the hakhsore kibbutz S-H.

Surrounding the kibbutz are well-cultivated, green fields. There are fine vegetable gardens and a substantial orchard— an orange grove. Several cows were pastured in a meadow, and the sounds of clucking chickens carried from the yard.

I went into a large courtyard. The grass had been cut. There were well-maintained flowerbeds and trees, lush with branches, cast shadows on the grass.

On the grass beneath the trees, there were young parents playing with their children. I greeted them, and sat down near the children.

The kibbutz was half empty. Half of the kibbutzniks were in the Negev, readying the permanent kibbutz. They come every two weeks to see their families.

My reception, as everywhere in Israel, was friendly and openhearted. Everyone was willing to answer my questions.

No one in the Kibbutz is more than twenty three years old. They are from…

p. 103

Aliyat Hanoar—from the Youth Aliyah. The largest number come from Egypt, with smaller numbers from Morocco, Turkey, and other countries. They have been in the country for two to three years. They all know Hebrew. Among themselves they speak a variety of languages: Arabic, French, and Turkish. But there was one girl there who spoke Yiddish with me. She came from Rumania. The girl wasn’t even eighteen years old. She’s been married almost a year. She was in Cyprus, and met her husband there. At first they communicated with one another through signs.

They took me around to show me their poor households. They led me through their dining hall, the children’s room, the children’s bedrooms, and then through their own huts.

They did not need a school for their children yet. None of their children are more than a year old. However, they did need a lot of children’s beds. They could not always afford to buy finished beds. The homemade beds that they have clapped together are something to look at.

“We are going to bring it all with us to the Negev,” they told me. “We will leave only the buildings and the two Singer sewing machines, for repairing old clothes, that we found in the big workshop when we came here. Everything else is ours. We worked for it. We expect to be in the Negev soon after Rosh Hashone.

“Why did we work the fields so thoroughly and plant such beautiful flowerbeds, if we are getting ready to move? OK, we are here temporarily, but the earth is permanent. Others will come in our place, just as we came once the earlier kibbutz went away.”

I sat on the grass with them, wanting to know all about why they came to Israel. Had they keenly felt the anti-Semitism in their countries? Were they escaping poverty? Did they come to build Yidn-Land? Were they uneasy about the fate of Judaism?

Most of them said nothing, but shrugged their shoulders. They did not know why they came. Some said to me:

“We were not told the truth. The leaders of the Youth Aliyah promised us the sun, the moon and the stars. Well, when we got here and…

p. 104

saw the real situation, we could not go back. We were not allowed. But now we are content to be here.”

Others said:

“No we did not suffer much from anti-Semitism up to now. But who knows what will happen tomorrow? In the end, they will slaughter us.”

A young woman who was as dark as a gypsy, holding a lighter-skinned boy in her arms, spoke up frankly:

“What use is a “Zionist sermon” to me? It’s good to live among your own people. It’s good to not have to carry the burden of Jewishness. Is that such a small thing—to be a Jew and not feel that weight? For me it’s more than enough.”

I spent until late in the afternoon with them. I met with them often over the course of the twelve weeks or so I was in Israel. My brother’s house was right on the way from the kibbutz into Ra’Anana. They would greet me when they went by, and often stopped to chat. It grew clear to me that this Youth Aliyah could not have come about merely through negativity. Maybe these young immigrants did not know it, but it was clear to me that most of them had come to free themselves from “Jewishness as an afterthought”. They were sick of living a double life – gentile the whole week, and Jewish for a few hours – and of bearing the yoke, the weight of a Judaism that made no sense to them. Here in Israel they could conduct themselves like the neighboring gentiles as much as they were able, and still not deny who they were. I believe this is probably the driving force for a lot of young immigrants.

——-

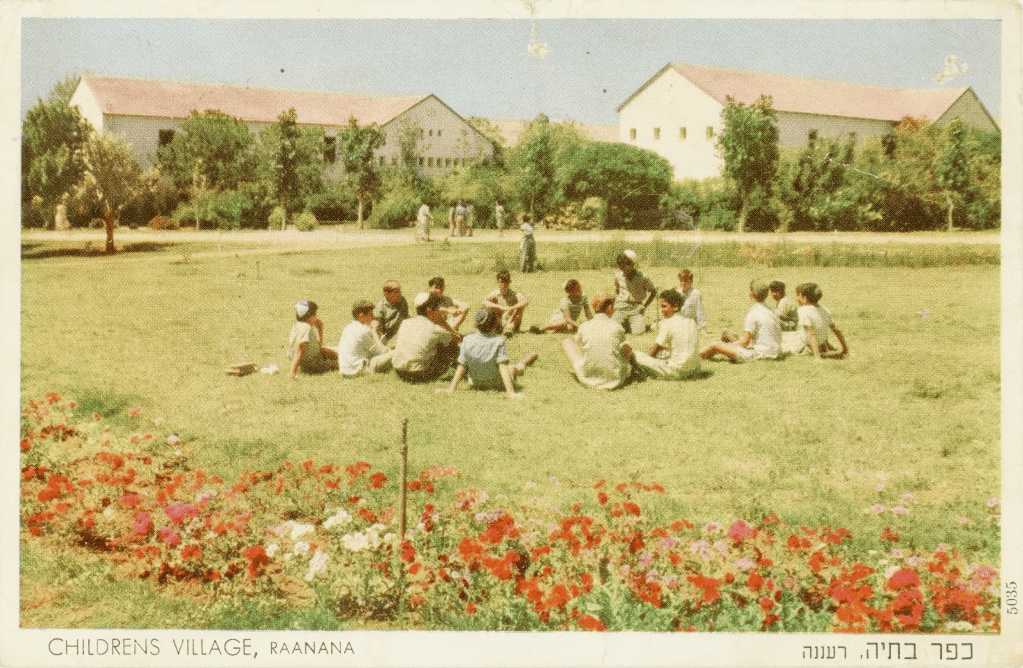

Around ten minutes away from Ra’Anana by bus, there is a children’s village. In America we would call it an orphanage, but in Israel this is not only a place where orphans, collected from throughout Europe, are supported or maintained. It’s a village where children are prepared to become citizens of the new Jewish people and members of the new economy. This is not just flowery talk. When you get to know this village, you see how exceptional and unique it is among orphanages.

p. 105

The village takes up a large area. I could not find out how much acreage it has. But I walked with a group for more than an hour, and everything they pointed out to me – there, that bit of ground, that field, that vegetable garden – belongs to the village.

The houses are marvelously well built. Of course, there is a beautiful children’s school, a synagogue, fine sleeping quarters, common areas, and play places. But there is also more: Stables with cows and horses, a garage with trucks and regular automobiles, a metal shop, and also cultivated fields, orange groves, vegetable gardens, and vineyards. The children work all of them. There were no outside workers there – only the instructors.

The village is supported by American money. I will not go into the details of how the village was founded, how the children were gathered or how the whole idea of the village originated. That’s not my point. What is important to emphasize is that the core principle is not just to help the children and to rehabilitate them physically and psychologically. That would be done in America, too. What is important is that the workers and the children view this accomplishment as important work on behalf of the nation. Every child feels that he has to pay back the people for supporting him. They look at themselves not just as saved children, but as saved Jewish children.

I walked around with two boys, one fifteen and the other sixteen years old. The younger one spoke Yiddish and Hebrew, the older French and Hebrew. We walked through a field and I asked questions. The younger boy spoke for both of them:

They would like to go to be in a kibbutz, but he, the younger one, has a mother, so he has to take care of her. The older boy has no one, but one of his hands is partly paralyzed and he does not know if he will be able to be admitted into a kibbutz. Both are studying radio mechanics. When they leave there, they are going to open a business together.

“Yes, they can do field work, they know their way around horses, they can take care of cows and chickens. Everyone has to be able to do that. Then, they can each choose their subject, their trade.

p. 106

“No, no one is making them speak Hebrew. They can talk to each other in whatever language they want. But Hebrew is spoken in the school, in the synagogue, in the workshops, in the field and stables, and around the chicken coops – because that is the only language the instructors speak. So it happens that Hebrew quickly becomes the language in circulation.

“Everything here is done by the children. No one forces them to work, especially at first, but before you know it, everyone is working together with his group.

“At age eighteen, everyone can leave the village. A few stay on as instructors. Most want to settle in the kibbutzim or moshavs in the frontier areas.”

I spoke Yiddish with the young men. The older one listened intently, trying to understand our conversation. Soon he did join in, addressing me in Hebrew:

“We will live in the cities if necessary. But we know that it is really important to settle the Negev and the other unpopulated areas. It’s not our fault if we cannot do it. And maybe later we will not live in the cities. We are still young.”

Later, I spoke with one of the teachers. He told me about the challenges they have had with

abandoned and neglected orphans. Many of them lacked the slightest feeling of social responsibility. They did not understand why stealing and cheating, when they were useful, were crimes. Punishment would not help. Just the opposite—if you punished them, they would consider the village to be a continuation of the concentration camp, and the teachers and instructors to be like camp guards and supervisors. What did have a powerful effect on them was to indoctrinate them with the idea that their bad deeds would shame the whole Jewish people. They must build a nation in order to gain respect… from the goyim. Naturally, we also surrounded them with love and faithful care. We saw to it that they had everything that they need and often not just what they need, but even what they want. Now there are practically no problem children here.

(click here to continue reading Chapter 11)