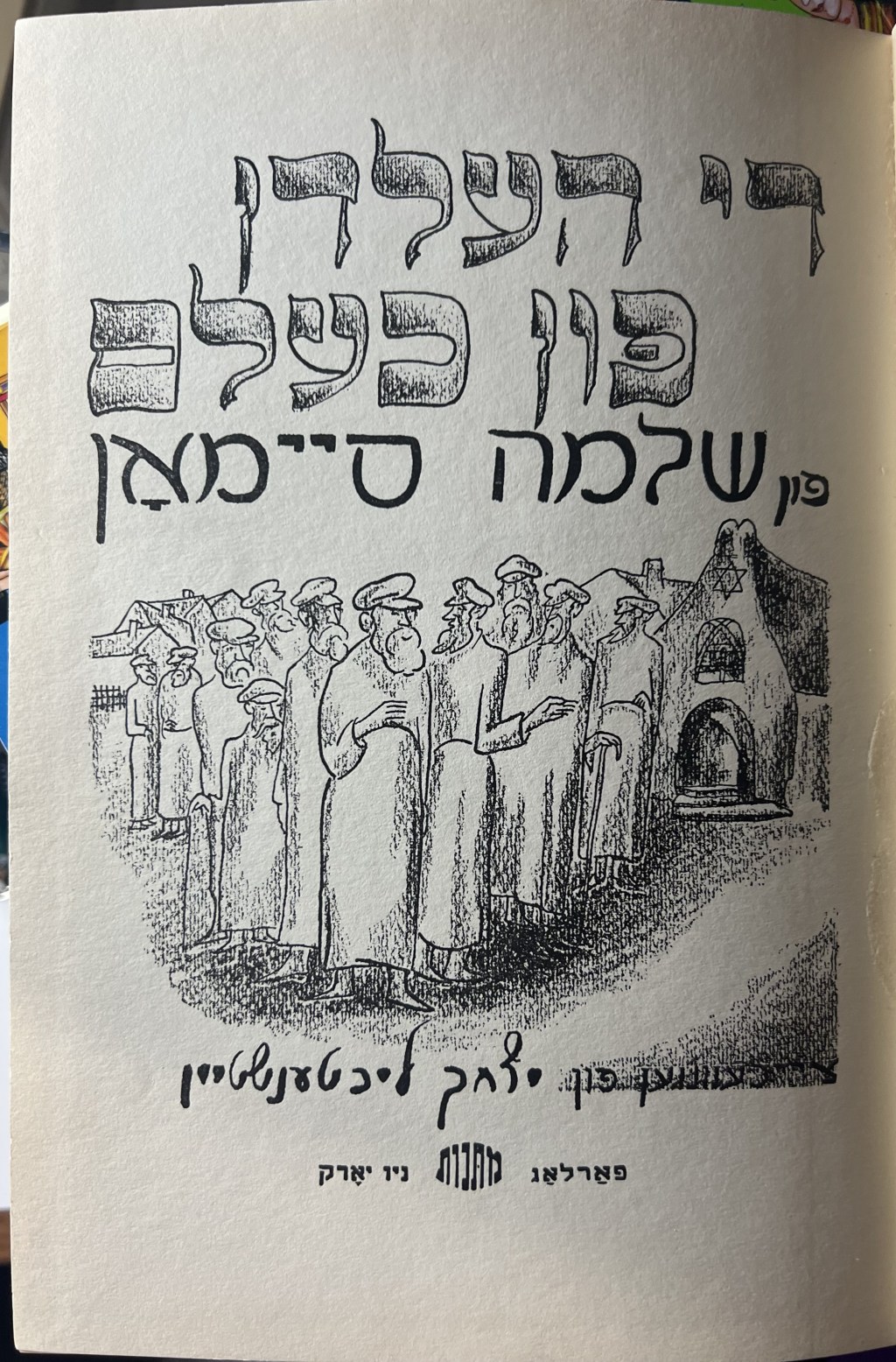

The Nation State and the Promised Land: An American Yiddish Writer in Israel, 1949, by Solomon Simon. English translation, 2024, by David R. Forman. All rights reserved.

Page numbers from Medines Yisroel un Erets Yisroel, 1950, Farlag Matones (NY), are included for those who wish to follow along with the original Yiddish, below.

To begin with the Introduction, click here.

I left my family in Haifa and set off alone to visit kibbutzim in the valley. It is rarely possible to take a bus from Haifa directly to the kibbutzim of the Jezreel Valley. I had to change buses in Afula.

Afula is a small town. Its businesses are located around the bus station. I had to wait a couple of hours there for a bus. I bought all the newspapers at a kiosk. A shoeshine boy, ten years old, was sitting between the little newspaper stall and a store window. I asked him if he shined shoes – a dumb question, but I wanted to start a conversation with him. He indicated with his hand that he did not understand Hebrew. I tried Yiddish. He did not understand. I began talking in English, and he answered with one word: “Hindi.”

The storekeeper came out, saw that I was wearing myself out trying to speak to the boy. He said to me:

“Your talking to him is useless. He comes from India. The whole family is here in an immigrant camp. He came to me two weeks ago, the poor little soul. I do not know how he managed to communicate with me. He has to support his mother, his sick sister and two little brothers. I thought he was trying to swindle me, so I got up and went over…

p. 120

to the immigrant camp. It’s actually true. Why were they brought here? I don’t have the faintest clue. Maybe they had designs on the children. So I let him shine shoes next to my store. The urchin makes his fifteen or sixteen piasters a day.”

The boy looked right at the storekeeper’s mouth, as thought he could understand his Yiddish, and smiled at him gratefully. As he shined my shoes, I talked with the storekeeper.

“You’re going to see the kibbutzim. Go, and see with your own eyes. You will see a group of scoundrels, lazybones, men with no ambition, fanatics who are always going on and on about matspun – conscience. You will see people who are content to live in one room, and to abandon their children to children’s homes, seeing them only a couple of hours a day, as long as they are taken care of in their old age. They are cattle! They want to be provided with everything and not to have to worry about tomorrow. You will see a meal, everyone in one room like in a poorhouse. No Shabbes there, no holidays. What a life!

“They have no future. All the kibbutzim were created by long-haired bachelors, their shirts tied with knitted belts with tassels at the ends. They wanted to bring the Messiah via Karl Marx. They do not believe in business or in the large manufacturers that can build a country. The new immigrants do not even want to look at the kibbutzim. Our young people are continually being brow-beaten: “Kibbutz! Kibbutz!” Everywhere: In the public schools, in the Mizrakhi schools, and absolutely in the agricultural schools of the Histadrut. But it doesn’t stick. They are taken to a kibbutz for three or four weeks every summer, and still very few young people become kibbutzniks.

Who wants to work like a slave and after twenty years, if you want to leave the kibbutz, they give you a two pound note and a pair of shirts, and – “Go!”? The future of the country rests in private enterprise, a little bit in the moshavs (cooperative villages), and mostly in the hands of individual farmers.”

I did not answer him. I just wanted to listen, not to argue with him. This was not the first time that I…

p. 121

heard an unfavorable opinion about the kibbutzim from a city person. But it was the first time I heard such a painfully sharp one.

Before the bus came, I still had time to have a conversation with the owner of the soda shop right next to the fenced-off area where people have to wait on line.

“How did I get such a good spot for my soda shop? No one gives you anything for free. I have been here for twelve years, and I have done my share. I am missing three ribs, and my left leg is shorter than my right. Been in my share of battles.

“I’ve worked chopping stones, laying roads, and in construction. I wore myself out. Now, thank God, I have begun to recover. My two boys go to school. The younger one is a truly good learner. I will make a pokid (a government worker) out of him. The older one will have to learn a trade. I want to send him to the Max Fein Vocational School. He will become a mechanic, and a person who masters a trade will not be at a loss.”

The bus arrived. We rode for just fifteen minutes, and the driver left me off at an unpaved road. He directed me to go straight on the road and I would arrive in M-H. A young man, twenty-two years old, got off with me. Yes, he was going to the kibbutz, too.

We walked between vegetable gardens and cucumber fields. I saw the road veered in between rows of trees in the distance—a decent bit of woods. To the left was wasteland and Mount Tabor.

—————-

Throughout the whole time I was in the Land of Israel, I would never remain tranquil when I came to a historic place. Passages and verses would start to jumble in my head, and they would bring figures and events up into my thoughts. Here, too: Mount Tabor is where Deborah the prophetess sat and judged the people. Here, at the foot of the mountain, an army mustered against Cicero. Not far…

p. 122

from there is Ein Dor, where Saul went to ask the witch to foresee the outcome in the coming battle.

It was quiet. The sun shone brightly and the air was clear. It seemed like you could reach out with your hand and touch that bare, barren mountain. It was a bright stillness, and it felt to me as though the echoes of Cicero’s army, and the reverberations from the ten thousand warriors of the tribes of Naftali and Zebulin, led by Barak, still remained in that barren place. I could actually see the petrified tree, there on the mountain, beneath which Deborah sat, judging the tribes.

———-

My companion spoke to me. “You’re going to visit the kibbutz?”

The illusion disappeared. I came back to myself and answered. “Yes.”

“Do you know someone there?”

I named an acquaintance I knew there.

“Oh, he is the principal of my school. He will get a fine room for you. It’s good that you, an American Jew, are traveling alone, without a guide, to get to know the kibbutzim. That is the right way to do it.”

I smiled and described what the storekeeper had said about the kibbutzim. My companion dismissed it.

“Nonsense! Who cares about the babbling of a storekeeper! The kibbutzim are the backbone of the Jewish Yishuv. In the war not a single kibbutz deserted its position voluntarily. The kibbutz is so constructed, that it is not only an economic stronghold for the country, but from a military standpoint every kibbutz is in fact a strategic position. If not for the kibbutzim in the Negev and in Sharon the armies of the enemy would have flooded Israel in ten days. Negba, Yad Mordechai, and Ramat Hakovesh won the war.”

p. 123

I did not say anything, and my young man grew more heated:

“Work is holy to us, and the equality of our members is the first and fundamental Mitzvah to us. The kibbutz is the owner of everything. The individual is not even the owner of his own room and the few pieces of furniture in it. It’s his for as long as he lives in the kibbutz. If he leaves the kibbutz, he is given two or three pounds, and he walks away with his clothing and his couple of books.

“But you have to understand, the members do not feel as though there is a power that rules unilaterally, and is the actual owner of all the kibbutz possessions. No! It’s a family. Do children feel that their house is not theirs? No, that example does not work, because children are sometimes mistreated by their parents. Better to compare the ownership of a kibbutz with the ownership of husband and wife. In a good life no one thinks about what will happen if one of them leaves the family.

“Look, there are kibbutzim with a thousand people and more. Yet there is no police there. They do not lock their doors at night. Now we have a night watchman around the kibbutz, but not in the kibbutz.

“The reason there are no police is that there has been no stealing, no violence, and absolutely no murder. Fighting, yes. Fistfights? Anyone who raises a hand against a comrade must leave the kibbutz.

“You have probably read enough books about the kibbutz. But in order to understand the relationship of a kibbutznik to his kibbutz, in order to grasp the absolute equality of the people, in order to understand our child rearing, you have to see it with your own eyes. You know the saying: Hearing is not like seeing. When you see with your own eyes, then you will believe what you have read and what you have heard.”

I wanted to ask him about himself, but we had arrived at the kibbutz, and he led me in to the secretary. I told the secretary that I had come to see Sholem. He called someone in and told him to find my friend for me.

p. 124

I received a wonderful welcome from Sholem, first because of the greeting I brought to him from his aunt and uncle, and second because he is a reader of mine.

Sholem comes from a good family. His father was among the most honored Jewish scholars, a leader of the Jewish Scientific Institute [Yivo] in Vilna. He died as a martyr in the war. His son was raised on Yiddish literature. He still reminded me of Vilna. I was happy to be with my first reader in Israel, even if a former one.

I asked about his wife. He answered, “She works in the laundry. The machine broke in the afternoon, so she will be working late, until eight thirty. We will be eating dinner late. Come to the dining room now, and we’ll have a glass of tea and a piece of bread with jam.”

I tried to refuse. He would not let me.

“I’m hungry, too. We still have a half hour before I will be able to see my daughter. Come!”

After our snack he went in to his room and got a bag of hard candies, and we went to see his child. He spent two hours with the child. After we parted with his child, there was still over an hour left until Sholem’s wife would be freed from the laundry. We walked past the large building and a short, thin young woman ran out and gave me her hand, which was wet and soapy. She apologized for not being ready until eight thirty. If we were hungry we should not wait for her. Then she ran back in. She could not leave the machine unattended.

Apparently, Sholem noticed that her exhausted, sweaty face and her fatigue, which was evident in her every movement, had not made a good impression on me. He said:

“Today was very hot, and then on top of that the machine broke, so she had to work longer. It’s very hard on her.”

We waited for her to eat. She sat with us at the table, but she ate very little. She was very tired. After the meal, she did not sit with us for long. When Sholem talked, she was quiet.

p. 125

…She could barely keep her eyes open. After sitting for a while, she excused herself. “Sholem will show you the kibbutz. I have to lie down to sleep.”

Later, he brought me to my room – a very comfortable room. We sat and chatted about a lot of things. He told me how he had come to the kibbutz. How it had taken a good bit of time until he adapted to that life. Then, how they had decided, against his will, that he should become a teacher. He told me about taking classes in the city, traveling home every week, and finally the war. He was what would have been called a first lieutenant in America, and he went through all the sufferings of the war.

He told me a lot of episodes from the war. What stuck with me was one short episode, which he described almost coincidentally, offhand, as one would tell an unimportant occurrence:

“We were lying in our position and exchanging fire. The enemy opened fire with a terrible hail of bullets. I lost six men in only a few minutes. By all the laws of strategy, we ought to have retreated. The responsibility of deciding what to do fell on me. I am afraid that, in that moment, I did not think about the fate of the Jewish people. It did not even occur to me that if we retreated we would open the road to Sharon to the enemy. I saw only one thing: If we retreated, they would have a clear path to take the kibbutz. They would go in and burn down the dining hall, the stables, and the children’s houses. They would destroy the machines, take the cows and the sheep, and we would have to go off. Maybe we would find a home somewhere, but what kind of life would it be without the kibbutz? No, retreating was not worth it. Better not to live to see such a time. We did not retreat.”

I spent several days at that kibbutz. It wasn’t one of the richest kibbutzim, but it was one of the extreme Mapam [left wing] kibbutzim, and I had a great many questions I wanted to ask. Primarily, I wanted to know about how they raise and educate their children. There was good cause to ask.

p. 126

On the first day I was at the kibbutz, I witnessed the couple of hours when the parents come to see their children after work. Work usually ends around four thirty. The first parents begin to see their children around five o’clock. I went off to the playground with Sholem.

The playground is right next to the children’s homes. It’s like a little park. The grass is mowed and there are trees ringing the whole space. The playground is equipped extraordinarily well: Swings, see-saws, a May pole, slides, and everything children ought to have for play.

Sholem was the first one there. His child ran to him with such joy and such force that she almost burst out crying. Sholem took the delightful girl in his arms, rocked her, and covered her with kisses. Soon more mothers and fathers arrived, each of them with something in their hands. The parents were so hungry for their children, that all of them gave in to their child’s every whim. And the children, who spent their whole day under the watch of trained caregivers, strangers, hired people, yearned for a stroke, a kiss and the indulgence of their parents. The children whined and the parents comforted them.

I saw painful scenes. Everyone stuffed their children’s mouths with candies, and it was only a very short time before supper. Children dragged their parents from one place to another. A three-year-old boy hit his mother with sadistic pleasure. The longer I sat there, the clearer it became that it was not a good arrangement. By the time the two hours were almost up, the parents and children were exhausted and restless. Several young children had actually become hysterical, and a lot of the older children sat resentful, angry or indifferent, bored with the time-limited affection.

I sat and took in all these scenes. I wondered how the kibbutzim were not raising nervous, helpless children. Whatever you might say about the sabras, nervous and helpless they are certainly not. Why not? I wondered that late afternoon.

p. 127

The next day I spent a whole day in the children’s houses. A lot of things about young people in Israel became clear to me.

The Children’s Houses are extraordinarily comfortable and well furnished. The children do all the necessary work in their rooms and around their apartment, to the extent that it is physically possible for them. Children wash their own floors, of course, and they clean and make their beds. They see to it that the children take care of themselves from a very young age. One trivial detail will illuminate this more, perhaps, than the most long-winded description. The three-year-old children have their own showers. The faucets have been installed at a height where the child can turn the water on and off himself.

Children only play in groups. I witnessed a scene where a three-year-old girl already had a feeling of group responsibility. The metapelet (caregiver) led eight three-year-old children to the playground. They walked, dressed only in pajamas. A girl fell hard and banged herself. She began to cry miserably. The caregiver stopped the group and quickly turned to see whether the girl was bleeding. She felt her to make sure no bone was broken. There was no danger. She said to the child, calmly, “Stand up, Ilona. It’s nothing!”

The girl cried loudly. The caregiver said calmly and quietly, “There is no blood. Stand up and come.”

The child did not stop crying and would not move from the spot. The caregiver spoke more sternly. “Ilona, you are holding up your class. They are all waiting for you.”

Ilona got up, rubbed her eyes on her pajamas and went off to the group.

From a very young age, the children have already become accustomed to a communal life. Upon reaching school age, each class has its room in the children’s home. They live together in the same room for all eight years that they learn in public school. When they enter high school, the whole…

p. 128

class is again given a separate room. And so the whole class of twenty boys and girls lives together for twelve years.

In the extreme kibbutz I was now visiting, the girls and boys slept in the same room until they were eighteen years old. In other kibbutzim, they sleep in the same room until the age of twelve. When I asked the caregiver, whether there wasn’t any immoral activity, when young people of that age slept together, she answered me:

“Not only do they sleep in the same room, they also take a miklachat, a shower, together. No, we still have not had any such unpleasant case here. But we are going to abolish the common dormitories for boys and girls over twelve years old. The reason is a different one altogether. The boys and girls here rarely fall in love. They look at each other as brothers and sisters. So, we have managed to make very few matches among our own young people. That will not do. They marry outside kibbutzniks and leave our kibbutz.”

I sat with the caregiver on the steps of the porch and spoke with her. Suddenly I heard a commotion, with a machine banging and strange cries, coming from behind a row of trees. I jumped up in fright. She stayed sitting calmly and said, “That is an instructor out with a group that’s on a tractor for the first time.”

I went off to watch what was going on there. Behind the trees, on the edge of a plowed field, there was a red tractor. About fourteen or fifteen boys were gathered around it and on it. A middle-aged man, who looked like anything you like – a Russian, an Englishman, a Scandinavian – but not like a Jew, stood in the middle of them, holding his hands over both ears. They were arguing about something having to do with the parts of the machine. Since I did not know the terminology, I did not understand a word of they were talking about.

Finally, the man gave a yell. “Sheket! (Quiet)”’

p. 129

When they had quieted down, he said calmly, “Chaim is correct.”

I stood off to one side and was only barely able to understand what the dispute was about. The group was not just learning how to operate the tractor, but also to understand the machinery. The instructor was the authority who resolved all differences of opinion.

Before I knew it, the group had found me and was peppering me with questions about American young people. The main question was, do the Jewish youth in America know about the war, which we just went through with seven countries? Are young Americans preparing to come to Israel? Is it true that there are quotas in American schools? Is it true that American Jews are afraid to read Jewish newspapers in the subway? What are the Jews in America waiting for, and why aren’t they leaving? A blind man can see that their fate will be the same as the fate of the Jews in Germany.

The instructor did not participate in the conversation. When I was left alone with him, he lit up a smoke and smiled:

“You see how it is with these kids? Well, they are not very well oriented to how it is in America. I was just there a year ago. I travel to you often. The party sends me, and I know the situation. Well, the guys have what you might call the Zionist perspective, which is oriented towards anti-Semitism. But, they are going to be kibbutzniks!”

He kissed the tip of his fingers.

The main industrial enterprise of this kibbutz is a large print house, which prints all of the party publications. I visited the printer. The workshop was equipped with the best printing machinery, most of it sent from America as gifts from members of the party. I was witness to a bad scene. A worker took a printed page spread off the press and, smiling, showed it to a young man who was sitting in the corner. I looked at the young man and recognized him as the one who had gotten off the bus with me the day before.

p. 130

He quickly skimmed the printed sheet and called out angrily. “That should not have been allowed to be printed! It’s not time to write these things yet! It’s a scandal!”

The typesetter, or pressman, taunted him. “It went through the editorial board.”

“If I had known,” answered the young man, “I would have protested, and I would have found a way for the press to refuse to publish it.”

I went up to the young man and greeted him. I asked him to show me the printed sheet. He gave it to me and said:

“Take it. Read. Be my guest. You are a writer and a man of the community. Read it and tell me. Should this be allowed to be published now?”

I read the two pages in question. It was a description of some really ugly things that Jewish soldiers had done. What made the writer angriest was that there were a lot of ‘Mapamniks’ among the soldiers. They were not better than the others.

I said to the young man:

“I think that you are wrong. One may write such things and, of all times, just now. It’s no great feat to publish such things years afterwards. You know that in times of peace it’s easy to be a pacifist. All “upstanding” people protest against the sins of the past. But the truly honest man calls out when the sin is being committed.”

He waved me off.

“Tonight we will meet and talk about it at length. In the meantime, do you want to see the kibbutz?”

“I like going around alone,” I answered, “but I would like you to take me to some of your friends in their rooms. I want to see where they live. I want to see if you really do have equality.”

He led me around. No one occupied more than one room. Those who had been there longest lived in better houses, but none of the rooms had an individual toilet or…

p.131

bathroom. The bathrooms were in the hall, in common space. Finally, he led me into a room, not one of the best ones, and remarked offhandedly:

“This room is Sh…’s, the Member of the Knesset [Parliament]. When the Mapai gives in to our demands and we have a coalition government with them, he will be our [Prime] Minister. But we will not give him a better room. He has only been in the kibbutz for ten years. These rooms are for the group with his seniority.

That night I sat with a number of active kibbutz members and we passed the time until nearly dawn. The cream of the kibbutz came to me. People sat on the bed, on chairs, on the floor, and on the sills of the open windows. I told them about America. An interesting conversation ensued. Afterwards, I began asking questions about the kibbutz. The first question was about the incident at the printer. It was not, however, the young man who answered me, but Sholem:

“This is not the time to talk about that. We did not want the war. The Mapam was completely opposed to a partition from the beginning. And we absolutely did not want to kick the Arabs off the land. But do you know what it means to lie in trenches for weeks and months, to be so tired that even breathing is strenuous work? You lie there, holding an old rifle, knowing that you could be cut into pieces any minute, cut up simply as that. You ought to have seen the bodies of our soldiers who fell into their hands. In such circumstances can you talk about matspun (conscience) and compassion, and following ethical rules? Oh, a lot of our boys paid them back with their own coin. Can you blame them?

But I did not let them off:

“That is, in fact, my complaint. Statehood has its logic. If you came here to occupy a country for yourselves, you could not have expected peaceful acquiescence from the existing populace. You must have expected that you would have to wage a war.

p. 132

“That’s true, in fact,” answered the young man, “our mistake was a much greater one. We did not create a Mapam movement among the Arabs. We were ready to make any compromise, but the Arabs did not want a compromise. Especially when the rich effendis exerted their influence, and then the international schemers did their part, too. Let them say that we were literally no better than the extremists. The only case of atrocities from our guys was no more than a result of that confusion.”

“No,” said another kibbutznik. “Self-criticism should cut to the quick. It’s good for the book to be printed. I am not proud of what we have done. There’s nothing to be proud of. Let there be a feeling of guilt. It’s healthier that way.”

After that matter, I brought up another question.

“Is the fundamental basis of your kibbutz materialistic, or ethical?”

Sholem shrugged.

“Begging your pardon, but that is just hairsplitting. As long as we have established equality in a just society.”

I tried to clarify my thought.

“Here in the kibbutz you have founded a very new kind of society. If there will ever be a socialist society in the world, or as I would call it, an ethical society, it will be according to your example. You have equality without the whip. You in the kibbutz are a kind of model society. You could influence the world. You live modestly, each of you only in one room, with the children in common rooms. Men, women, and teenagers all work. There are no freeloaders among you. You have altered family life, and you have minimized poverty. You have full democracy, both political and economic, and I repeat, without coercion. Moreover, every one of you bears social responsibility. You spend the capital you have saved, due to your low standard of living, on three things: a very small portion on…

p. 133

small luxuries for the members, a large portion on bettering the kibbutz, and a very large portion for the good of the whole [nation]. One example: Your poor kibbutz supports over two-hundred children from the Youth Aliyah—immigrant children. And two hundred children a summer come to you from nuer-oved, which I suspect that you also have to lay out money for. So, imagine there is no more Youth Aliyah. The empty land is settled. There is no longer an economic need to keep the children in common dormitories in children’s houses. The mothers do not have to work as much as the fathers. Will you maintain the communalism of the kibbutz? No, it seems to me.”

“But,” I continued, “if the basis of the kibbutz is an ethical one, where ‘people are not allowed to live in too much luxury, children must live in homes rather than with their parents, everyone must work for his bread,’ then the kibbutz would stay the way it is now. Of course it would change with the times. In other words, Jewish ethics say, Live in such-and-such a way in order to lead a holy life, because human beings are holy. The materialist Torah teaches, Live in such-and-such a way, in order for the future to be comfortable”.

The young man I had met in the bus smiled.

“You are a Jew who loves to split hairs, but there is a lot of truth in what you are saying. Still, your pilpul is a matter for the distant future. For the next fifty years, there’s no reason to have any fear. The Negev and the Galilee are unsettled wilderness and cannot be built up with private capital, or even by cooperative Moshavs. The country must have kibbutzim, a lot of kibbutzim. So, without theoretical hairsplitting, we need to raise a generation that will want to live the ascetic life of a kibbutz, and in particular the difficult life of a young kibbutz.”

We talked about many other things. I cannot relate all of them here. But one opinion, even though it had to do with me personally, is worth recording.

I visited the library. I examined the children’s library very thoroughly. I was struck by three series of books translated from English: Dr. Doolittle, The Wizard of Oz, and Adventures of Tarzan.

p. 134

I complained to them.

“These three series are very cheap books, books with practically no literary value, particularly the series about Tarzan. And yet you have eleven volumes of precisely that series, and five copies of each volume. How can this be?

And here a man sitting on the open windowsill answered me:

“The Tarzan books are right for us. They have adventure stories, fighting, battles and personal courage. Now we have to plant such character traits in our children. For us, this is an era of fighting. You know, Dr. Simon, I did not want to say it to you, but I am very well acquainted with your children’s books. I am an official librarian for the children’s section. I want to compliment you (and here he began praising me to the skies). There were recommendations from America that we translate your books, but we are not going to translate them. Your Goles-Yidn[1] are too much the fine Jews for us. Not only is your “Shmerl the Fool[2]” not a fool to you, but even your “Heroes of Chelm” are no idiots. You don’t laugh at them, you idealize them. For you, they are dear, clever, upright, and deeply honest people. We do not want our children to view Goles-Yidn this way now. Now we want to denigrate the Exile. We print Mendele, who makes fun of the Jews. We print a lot of Sh. Ben-Zion, who hated the shtetl. Thirty or forty years from now we will translate your books. Now, it is too soon.

Again, we passed the time together until the wee hours of the morning. We went to the dining room and ate breakfast. Then I went off to sleep. The kibbutzniks went to work.

(click here to continue reading Chapter 13)

[1] Goles-Yidn. “Exile-Jews”, a Zionist term for Jews of the diaspora.

[2] Shmerl the Fool. The protagonist of of Simon’s book Shmerl Nar, was Shmerl the Fool in Yiddish, or Simple Shmerel in the English translation, The Wandering Beggar. Di heldn fun khelm (The Heroes of Chelm) appeared in English as The Wise Men of Helm and their Merry Tales.