Chapter 11 marks something of a shift in tone. It’s true, there is more on the themes he has already been developing – his amazement at the Biblical landscape come to life, his discomfort with the Israelis’ militarism, with their cavalier attitude towards the Arabs who were just displaced and with how, even now, some Israelis were actively awaiting a chance to expand their territory (as shown in a children’s school project). There is continuity, too, in Simon’s interest in the changes Hebrew was undergoing and his complaints about the buses.

What’s new is that he is finally delving into the day-to-life of the kibbutzim.

Simon was ardently anti-communist and against violent revolution, but he was also from an extremely poor family. He came from “Bal-mlokhes” — artisans and tradesmen. His family escutcheon was comprised of carpenters, wagoners, tailors and shoemakers all the way back. He had escaped the grinding and poor-paying labor of the rest of his family members through his gifted intellect. He was the only one of his siblings who continued his formal education in Russia past age 13 by attending Yeshivas, and when he came to America, he graduated from a combined college and dental school program and became a professional dentist. But he never lost his sympathy for and sense of identification with common working people.

In the kibbutzim, he witnessed “true democracy (both political and economic) without the whip”. He was very moved. It seems to me that up to that point, he had mostly been asking which of the values he admired in traditional Jewish life were being retained and which were being discarded by the Israelis. Now there was a different feeling — that the Israelis had created something new that could benefit the rest of the world. He had already noted his hosts’ idealism (but in service of ideals that were mixed in their appeal to him), and also their willingness to sacrifice. Now he saw that energy harnessed towards something about which he had fewer qualms or no qualms at all. The ideal of equality.

He recounts visits to numerous kibbutzim of different ideologies and in different locales, not just in chapters 11 & 12, but also in the three chapters that follow, to highlight the achievements and problems of these new “model societies” for his American audience. As usual, his admiring something does not preclude him from criticizing it when he feels the need. All in all, Simon devotes nearly a third of the book to the subject.

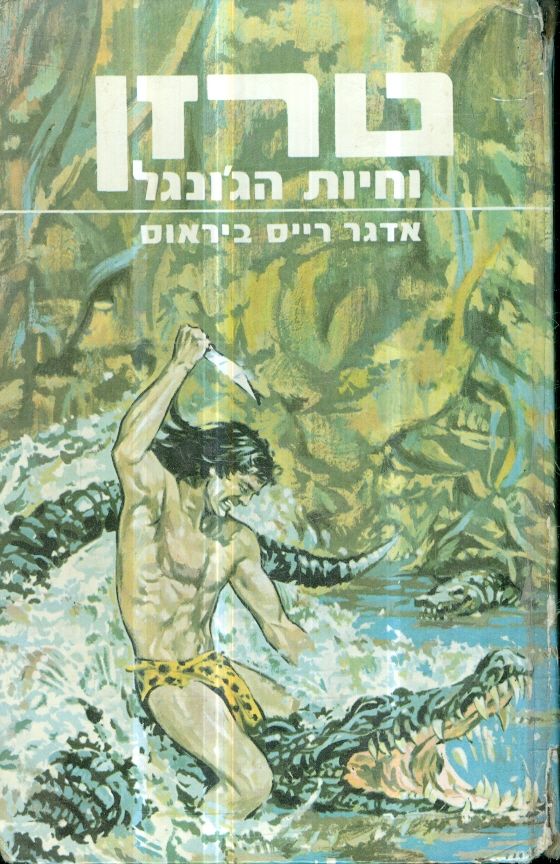

Chapter 12 ends with another moment that struck me deeply, a vignette that I find really heartbreaking. In his conversation with a kibbutz librarian, he learns what the Zionist concept of the “negation of the diaspora,” meant when it came to his own work as a Jewish children’s book author. Among the books he had published for children in America, two in particular had been very successful. Shmerl Nar (The Wandering Beggar) and Di Heldn fun Khelm (The Wise Men of Helm), were grounded in European Jewish folktales but transcended their source material and created something new in Jewish children’s literature[1]. Both had been translated into English and would also seem to have been perfect material to translate into Hebrew for Israeli children. The problem? Simon had too positive a view of Jewish culture in the diaspora, and of the people who embodied it. The Israelis thought that Tarzan would make a better role model.

Finally, a heads-up. There are a couple of bits in the upcoming chapters, 13 and 14, that will seem racially insensitive by current standards. The point of this project is not to idealize the author or present him as some kind of prophet. I’m against revising history through subtraction unless something is hateful. These don’t qualify, but there will be a moment or two you’ll be reminded that we’re dealing with a man who is the product of his time, and that time was 75 ago.

[1] In the ‘unbiased’ opinion of the writer’s grandson, who grew up on these books.