The Nation State and the Promised Land: An American Yiddish Writer in Israel, 1949, by Solomon Simon. English translation, 2024, by David R. Forman. All rights reserved.

Page numbers from Medines Yisroel un Erets Yisroel, 1950, Farlag Matones (NY), are included for those who wish to follow along with the original Yiddish, below.

To begin with the Introduction, click here.

I met and spoke with a lot of observant[1] Jews in the State of Israel. They have dozens of complaints and demands, both to the government and to the populace. Their primary complaint is, “Lo yayse ken b’Yisroel”— one does not conduct oneself this way or live this way in Yidn-Land. To come to the Land of Israel and live a goyish life, without Torah and without Mitsves, they argue, is meaningless. To live in the Land of Israel is a privilege. Jews have a duty to be more observant and God-fearing.

The general population does not, heaven forbid, prevent the observant from their practices. But it is clear that if the observant got power, they would prevent the great majority in Israel, which is far from religiously observant, from living as it wishes. The observant want to force a strict Sabbath on them, to institute a different school system and to impose the rules of kosher food in public places. In general, they would have the Shulkhn Orekh[2] be the legal framework for the country.

On the surface there does not seem to be any difference between the secular Jews and the observant. Naturally I do not mean the ultra-orthodox. They all dress similarly, and speak Yiddish and Hebrew. Their school systems are almost the same. But this is only on the surface. At bottom, there is a large gulf between the two worldviews. Let’s take, for example, the public school.

I visited a Mizrachi[3] school and a common school. Fundamentally, there is a gulf between the two schools. In the common school, the ‘external’ subjects…

p. 161

like geography, natural science, literature, history and mathematics are the core subjects. Tanakh and Mishnah are a kind of supplement. In the Mizrachi school, Tanakh, Mishnah, and Shulkhn Orekh are the core subjects, and the external subjects are the supplement.

One illustration: In the public school, I saw a lot of children’s projects. The projects were the same as in the American public schools, but in Hebrew. In the Mizrachi school, the children’s projects were only about Torah, about Jewish customs and laws.

The first and second grades in the Mizrachi school had completed a large project about Bries-oylem, the Creation of the World. There was a large rectangular board, with a hole in the middle, and a child showed me what God had created each day, putting the correct picture in the hole in the board.

I saw a project about the pare adume [the red cow]. First the difference between a duty and a Mitsve was described, with lovely Torah-script handwriting, giving the passage of Rashi that discusses the second verse of Parshe Khukas[4]. Then it described how the red cow would be bought and prepared. There were also the stories from the Talmud about the red cow. After that, the two pages of the Gemore [Gemara], one listing the commandments of the Torah that are like decrees from God which cannot be questioned, because human understanding cannot grasp them; and the second page listing the commandments that have a reason, an explanation that human understanding can grasp why God gave them.

The m’naheyl (principal), a Litvak with a tall figure and a rabbinical ordination, lamented to me that the state does not support the religious schools as generously as the general public schools. The elites do not come to their school events, and other complaints. In general, the observant Jews feel a little bit in exile in the State of Israel.

In fact, he was not right. The support given to the religious schools is not less than that to the general schools. The fact that the intelligentsia do not come to their celebrations in the orthodox schools is simply because the intelligentsia are not orthodox. They feel as though they are in exile because they are a small minority. The broader population is far from being observant. For example, it’s…

p. 162

a lot harder to find a kosher restaurant in Tel Aviv than it is in New York. The masses are not interested in kosher observance. The broad population does not want to keep Shabbes in the orthodox manner either. The observant see people driving private cars and taxis on Shabbes, and consider it to be a scandal. The general population, however, does not like that the observant sector has been allowed to close the cinemas and stop bus traffic on Shabbes.

The conflict over observance is the only conflict between the two groups. On other basic questions, there is no trace of conflict. The stance towards refugees, the manner in which the war was fought, the economic postition of the government, the question of Jerusalem – on all these points there is unity.

The urban orthodox Jews do not have special problems or difficulties. After all, their life in the cities and towns of Israel is no different than life in cities all over the Jewish diaspora. What’s more, it is easier for observant Jews in the State of Israel to keep their Jewishness. Shabbes is the official day of rest. There is not a non-Jewish [majority] population to which one must adapt economically and spiritually. Education can be more completely Jewish. The economic circumstances do not force children to devote time to learning a foreign language or with studies that are not Jewish.

But it is different in the kibbutzim. There are a lot of challenges for the observant element there. It is hard to keep Shabbes on a kibbutz, where the economic life is tied to agriculture and animal husbandry. The question of shmite [laws regarding the sabbatical year] is not thoroughly resolved, and leket, shikkhe, and peye, are also difficult commandments to uphold[5].

Therefore, I very much wanted to go to a religious kibbutz. I wanted to see their customs with my own eyes and talk with the kibbutzniks in person. But something delayed me every time.

A week before I left Israel, it happened that a relative of my sister-in-law, who is a teacher in a religious kibbutz, invited us to her wedding. My sister-in-law comes from a very prominent Hassidic family, and has connections to the religious sector. I was very happy to have the opportunity. I was…

p. 163

especially happy that the kibbutz bore the name “Khofetz Khayim.” I have a connection to the Khofetz Khayim[6] – I studied in his Yeshiva in Radin and ate my Sabbath meals at his table for a full year.

We left for the wedding on Thursday afternoon. To write out the words “we left for the wedding,” or to say these words. is easy. But the trip itself was a whole adventure. Normally, the bus goes there once a day, at eight o’clock in the morning. Now, because of the wedding, a special bus had been ordered. “Egged,” the cooperative that has a monopoly on transportation to southern Judea, could not spare more than one bus. One “special” bus cannot take one hundred people. However the bus was packed, forty people would have to be left out, and the kibbutz had to send a truck for them. So, don’t even ask what happened at the bus station. I got in because of my older in-law, the mother of my sister-in-law. She is a ninety year-old woman. She with her highest status, could bring her guests. I held onto her hand and got in with my wife and daughter.

The trip in the packed bus was actually pleasant. Despite the mass that had squeezed itself in, everyone was polite and in good spirits. The crowd felt itself at home with its own. People knew each other and called each other by their first names. Also, they were happy – they were going to a wedding. People exchanged jokes and witticisms and then began to sing. When they were talking, people talked exclusively in Yiddish, except that when someone talked to a child, they spoke Hebrew. The singing was all in Hebrew.

At the beginning, the singing was a little slow. Only the men sang. I was surprised and did not understand what was happening. True, a lot of women were dressed with their heads covered in scarves. But the scarves were tied around their heads so coquettishly that it had not occurred to me that only married women were wearing scarves, and they hid their own hair.

I started to ask for the women to help us out…

p. 164

in singing. They hesitated. A Jew with an ascetic appearance and with a flat, thin beard, got angry. “Kol Shebaish—a woman’s voice is obscene.”

But here the old in-law interjected, the one with great status:

“No matter. It’s OK. Since we are going to a wedding, everyone may sing. Sing, daughters!”

And they sang. Everyone sang. I have never heard such warm, heartfelt, and varied song. They sang pioneer songs, Hebrew folk songs, popular radio songs, and parts of bible passages and prayers.

That was how we arrived at the kibbutz, with songs in our mouths. On our arrival, we were met by children in yarmulkes, yelling and clamorous. They chased the bus until it stopped, and they sang along with us. I must confess: The children got to me. That I might suffer instead of thy dear little bones! It has been a long, long, time, close to four decades, since I have seen children running up to welcome wedding guests.

The guests poured out of the bus and there was hugging and kissing all around. Before you knew it, men women and children were in a ring of Hassidic dance. Of course, the women danced separately. Even the little girls danced only in the women’s circle.

People were all danced out. But it was still too early for the wedding. Then, too, a lot of relatives were still missing. We had to wait for the truck with the rest of the in-laws. The crowd went off to look at the kibbutz. I stayed near the dining hall, which was open to the clear sky. A huge swath of ground, fifty meters long by fifty meters wide, was paved with asphalt. Tables and benches, made out of stones and cement, had been installed on it. The tabletops were made from one piece of stone. I stood and marveled at the primitive beauty of the work, and at the same time thought to myself: What do they do in the rainy months?

p. 165

A young man with a red beard and not very long peyes materialized beside me:

“I see that you are wondering about our dining hall. We cannot help it. We took over three quarters of our old dining hall as a synagogue. We do not have enough money for a new building. So, we built a dining hall in the open air. There are big problems in onot hagshamim (the rainy season). We try to spread a tarp over the tables and benches. But the Israeli rain could go through boards, let alone through linen. We suffer.

He led me into the small dining room that had a roof. On one side was the roomy synagogue, and on the other side, the large kitchen. The middle room, which could hold only about fifty people, was not just a dining room, but also a library. There were shelves from the floor to the ceiling, stuffed with religious books. I surveyed the books: Talmuds and more Talmuds. You could see they were not just there for the sake of appearances, but were really being studied. There wasn’t just a complete edition standing there the way libraries have them, but the books were separated by tractate. The most popular tractates of orders Nezikin, Moed, and Nashim had at least a dozen and more like twenty copies of each tractate. Of the less popular tractates, which are studied less often, there were two or three copies each. There were also a lot of books of commentary, like the books Pnei Yehoshua and Shita Mekubetses. And there were ethics books: Mesillas Yeshorim, Chovot HaLevavot, Chofetz Chaim, and a lot of other books from the publisher “Mossad HaRov Kook”. These books were not new ones. The covers were torn and the pages tattered.

“I see that people study avidly here,” I said to the young man.

“Thanks to his Blessed Name, we study a little. But you know that study is one of the three things that have no limit and no measure.”

Meanwhile, my wife had come in, and she said to me:

“You must come see the bride’s room. You have never seen anything like it in your whole life.”

“What is so special here in this kibbutz, that I have never seen it in my whole life?”

p. 166

“Come, see it with your own eyes, and you will admit that I am right,” my wife said.

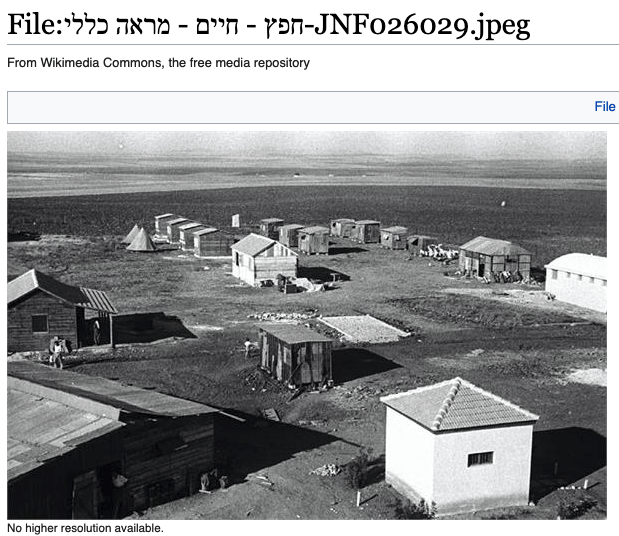

I excused myself to the young man and went with my wife. Yes, it was, in fact, something to see. The bride’s room was four fingers long and two fingers wide. The kibbutz had made her an apartment out of an “elevator.” An elevator simply meant a large crate. A lot of machines come to Israel from America. The machines are sent in large wooden crates. People take the crates and set them up on their narrow side. They cut out holes for windows, and a larger hole for a door. The crates are covered with tarpaper and… you have an apartment.

I stood there and marveled at the devotion with which the crate-room had been decorated: Whitewashed in two colors, the floor colored red and the little windows decorated with curtains. The furniture consisted of two beds, a small table, two chairs and a pair of shelves with some books. Everything was neat and clean, a true dollhouse. It was lovely to look at the apartment. But how someone could live in such a tiny room, I do not know. Later, after the wedding, I spoke with the couple. I could literally feel their piety, simplicity, commitment to the kibbutz, and great love for the Torah. I knew that they would be a lot happier in their crate than a lot of people who live in mansions. And it absolutely will be a real Jewish home.

The wedding canopy was erected. For young men held up the spread-out four corners of a tallis for a chuppah. Two women from the kibbutz escorted the bride. My old in-law, who was standing next to me, gave a sob and whispered:

“She is the only one left from her whole big family in Poland. May God grant her health and long years, and may she found a new generation of God-fearing Jews.”

The groom was brought to the chuppah. I nearly fell off my bench. His figure was indescribable. But that is not what surprised me: Beauty is a gift from God. But his clothing: He wore brown sport pants and an “Eisenhower” jacket, which made his fine…

p. 167

figure even more evident. Brown, shined shoes, a white shirt with a bow tie, a blue yarmulke on his head, and a silk tallis thrown over his shoulders.

The women guests opened their eyes and their mouths wide: “Keyn eynore, what a handsome man!”[7]

Later I learned that the beautiful and pious bridegroom is the sports teacher on the kibbutz.

The wedding ceremony was short and flew by. Soon after, the singing and dancing began. The men and women danced separately. They danced a hora, and the men sang. The women danced quietly, but one one woman accompanied the dancing with a harmonica. They did not sing any kibbutz songs, but they set verses to kibbutz melodies. First they sang verses from Jeremiah 33. As the crowd set up and linked their hands across their shoulders, a fifty-year-old, with a trimmed black beard began the song

Od yishomah bamokom hazeh[8]— “There shall again be heard in this place…”

The crowd rocked, danced and answered with a horah melody:

Kol soson vekol simkho, kol khoson vekol kalo– “A voice of gladness and a voice of joy, a voice of a groom and a voice of a bride.”

They danced and danced, stopped for a while, swayed and the Jew with the trimmed beard sung out again:

Kol umrim— “A voice of those who speak.”

And the crowd started dancing a new horah and answered:

Hodu es Adonay tsevaos, ki tov Adonay ki leyoylom khasdo— “Praised be the God of Hosts, because God is good, because His mercy endures forever.”

Done dancing these passages from Jeremiah, they sang out verses from Psalms 118:

Kol rino viyeshuo beoholey tsadikim— “A voice of song and help in the tents of the righteous.”

Then they sang their own version of the well-known kibbutz song.

“Hava netza bimechol…”

p. 168

“Let us dance, let us dance around for the work, for the kibbutz, for the defense [the army], for the training. “

A journalist who sat next to me made fun of them.

“Khnyokes.[9] Look how uncreative they are. They do not even have the wherewithal to create their own songs. They take everything from ready-made songs, from old verses and clichés.”

I turned my head away from him. I sat and looked in the distance. We were in Southern Judea. The kibbutz was a green dot in the wilderness. Jews had come from Hungary, from France, from Lithuania, from Russia and Poland, and returned to settle this ruined land, this barren ground. How can they stop marveling at this great miracle? Jeremiah’s prophecies were living words in the mouths of these, the gathered-in of Israel:

God spoke, saying, “In very this place where you have said– It is barren, without people and without livestock, and the cities of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem, which are deserted, without people and without inhabitants— will again be heard a voice of gladness and a voice of joy, a voice of a groom and a voice of a bride, a voice among those that say, Praised be the God of Hosts, because God is good, because His mercy endures forever.”

One would have to be a hard-bitten journalist, or a rational robot, to not be moved by the singing of these verses sung in this tiny settlement in Judah in the middle of the wilderness. They see God’s hand in the wonder that has happened before their own eyes. For them, Jeremiah’s words are not just old songs, set down in an old book. They are the living words of a living God. Let the non-believer hold his tongue!

The crowd was told to come sit around the tables. I wanted…

p. 169

to sit among the kibbutzim. I was not allowed, and we were shown a place at the front, near the groom. My wife was seated at a different table, with the women, near the bride.

We were given a good meal: Fish, soup, roast chicken and compote. As my habit is, I did not sit still in one place. In the middle of the meal I went over to the table where the young man with the red beard sat, among the kibbutzniks. I saw that they were eating a normal poor weekday kibbutz meal. The young man told me:

“We eat fish and chicken only once a week – on Shabbes. So, eating fish and chicken twice in one week is too big a luxury for us. We do not want to make a weekday into Shabbes, whether there is a wedding or not. However, we made a wedding meal for the outside guests. We wouldn’t want, Heaven forbid, to embarrass the bride and groom.”

After the meal we said the blessings as a group. The kibbutz rabbi stood up and gave a talk. He praised the groom for his piety and for his drive to learn Torah. Then he began his pilpul [discussion of fine points of Talmudic interpretation]. The crowd not only sat quietly, but hung on the rabbi’s every word. The journalist somehow reappeared next to me and whispered in my ear:

“Country or no country; war or no war – the old idle nonsense.”

I asked him not to bother me. It was hard enough for me to follow the rabbi’s brilliance. The journalist teased me:

“The Yeshiva bokher[10] from Khofetz Khayim has reawakened in you.”

Next, the children gave a presentation in honor of the bride and groom. I sat very close to them, but I could not catch the meaning of their satire. It all had to do with the bride and groom, about their work in the kibbutz, and apparently also jokes about certain customs in the kibbutz. I sought out the man with the red beard and asked him if he wanted to stay there or go somewhere and chat with me. He went with me a bit farther away from the dining room and we talked:

“Feeding the cows and chickens on Shabbes is permitted according to the law. It is an act of compassion for a living creature, after all. As for milking the cows on Shabbes, they are milked with a machine that is set on a timer. Yes, in a lot of religious kibbutzim they are milked by hand, but they do not use the milk…

p. 170

directly – only what comes from the milk: cheese, sour cream and butter. There are mekilim [lenient rabbis], but here on the kibbutz we are among the makhmirim [rabbis who interpret strictly].

“The question of shmite? Two years from now, when shmite arrives, we will observe the shmite. Over course it would be good if we had a diversified economy. In the sabbatical year we could draw our sustenance from a factory. But we are poor, and we will have to depend on assistance. Yes, it is a poor kibbutz. Before us, it was a Shomer Hatzair[11] kibbutz. They relinquished their charter, and we took over the ground five years ago. It’s been hard. There was not enough land. Now, praise His Blessed Name, after the victory we have enough land, vineyards and orchards.

“Conquered the land by the sword? We did not conquer it. We did not come into a foreign country and take the inhabitants’ land away by force. We returned to the Land of Israel. Seven countries attacked us, just as in the past: The sheva amim.[12] We fought a war against them and, thanks to His Blessed Name, vanquished them. It is not written anywhere that one is not permitted to fight a war. It was a just war. We did not go and start a war to enlarge the borders of the country.

“In our kibbutz we do not have anyone from the Youth Aliyah. We are too poor to support them.

“Yes, we have a Talmud study group, a Mishnah group, even a group for Psalms. But to tell the truth, we cannot study as much as we would like. We have to work hard, and we are tired. But we carve out time, and we have a whole day to study on Shabbes.”

The crowd was still celebrating and carrying on, and we kept talking. When he found out that I had studied with Khofetz Khayim and eaten at his table on Shabbes, he was delighted. He suggested that we all stay for Shabbes.

“You have no tallis or tfillin? So, in the morning, there are two minyans, You can use my tfillin. We have taleysim for guests. On Shabbes, you will hear a discourse on the Gemara, and see how we observe Shabbes here.”

The partying was done, and the evening prayers began. After the evening prayers, it was announced that those who wanted to stay over should sign up, and they…

p. 171

would be given tents. For those who wanted to go back, a truck would take them at eleven o’clock.

I signed up to stay overnight. The young man excused himself:

“I would keep talking with you longer, but I have to go on guard duty tonight.”

A truck arrived. The kibbutzniks set up benches on it, and those guests who wanted to ride back to the city began getting on. The kibbutz gathered around the guests to say goodbye. They parted with a song. The crowd sang the verse from Psalms:

Yemin Adonay romemo, Yemin Adonay yoso khail—God’s right hand is uplifted, God’s right hand does great deeds.

When they sang the words “God’s right hand is lifted” the red-headed young man along with two other men who were standing with rifles, ready to go on guard duty, raised their rifles into the air.

The bus started to move. Everyone, in unison, called out their farewell: “Shalom, Yidn! Shalom Yidn!”

My wife and I were given a tent to sleep in. There was no light in the tent. We felt around in the darkness and found two army beds without bedding and without sheets. Each bed had a sleeping bag. We undressed, got in the sleeping bags and pulled the “zipper” up to our necks. We closed our eyes.

I could not fall asleep. I pictured the Yeshiva of Khofetz Khayim in Radin and the hundreds of bokhers there as though they were alive in front of me. How would they, those yeshiva bokhers, have fitted in here? With great effort, I could imagine that those ecstatically pious young men, great students and moralists, might have been able to drive a tractor and milk cows. But there was no way that I could reconcile those bokhers, who used to sing portions of The Path of the Just and Duties of the Heart in the evening, with holding rifles on their shoulders. It is a rupture in Jewish history. Here the pious Jews who till fields, cut grapevines, sow potatoes, who know how to get along with cows and horses, and who are not afraid of rifles,…

p. 172

and machine guns cannot remain the same unworldly zealots as the Yeshiva bokhers from the Khefets Khayim Yeshiva in Radin.

I smiled to myself, as a strange thought occurred to me:

It’s possible that some day this kibbutz will raise horses for the track, bring them to market and even ride them in horse races with gambling. How would this jibe with The Path of the Just and Duties of the Heart, with the Shita Mekubetzes and the Pnei Yehoshua, and with their beards and peyes?

Jackals could be heard howling in the distance. Field mice ran into and out of the tent. I rolled over from one side onto the other and could not fall asleep. Finally, I dozed off. My wife shook me.

“Shloime, get up. A mouse ran over my face.”

I answered her. “Go to sleep. It’s nothing. There are field mice. We are next to a field.”

My wife answered, trembling:

“I am afraid to go to sleep. I often sleep with my mouth open. A mouse could go in my mouth.”

We waited out the night. At the break of day we got dressed. My sister-in-law in her tent had not been able to sleep either because of the mice. A bus drove by the kibbutz at six o’clock in the morning. We left with that bus.

I was not destined to hear the rabbi’s Talmudic discourse nor to see the young man with the red beard and study a page of Gemara together. He was surely disappointed. Me too. Apparently, the Yeshiva bokher had, in fact, reawakened in me.

[1] They Yiddish word frum has no exact English equivalent. Applied to individuals, it can mean ‘observant’ or ‘pious’ (in both senses of the word), or it can be applied to groups to mean Orthodox Jews, in contrast to members of more liberal Jewish denominations or to secular Jews. Haredi (or “ultra-orthodox”) groups were a very small part of the population in 1949.

[2] Shulkhn Orekh, (often transliterated from the Hebrew as Shulchan Aruch). See note to chapter 14. Used there ironically, here literally.

[3] Mizrachi here refers not to Jews of Africa and the Arab lands, but to the religious Zionist movement originating in Eastern Europe that founded a religious school system in Israel.

[4] A weekly Torah portion, from the book of Bamidbar (Numbers), 19:1-22:1.

[5] The list includes rules concerning gleaning– the margins of the fields, and of portions of the crops that are forgotten or missed at harvest, which are required to be left in the fields for poor people.

[6] Chofetz Chaim [spelling varies]. A name given to Israel Meir Kagan (1839-1933), after the title of his book.

[7]keyn eynore, “[may] no evil eye [befall him]” is said before praising someone or describing someone’s good fortune, so as not to tempt fate, or demons.

[8][DRF] Spellings of the Hebrew in this section are inconsistent. Simon was clear about his preference for the Ashkenazi pronunciation, especially when it came to the source texts. I do not know how these songs would have been sung at the time in a religious kibbutz in Israel, where the singers would have first learned these verses in a religious school. Nor do I know how Simon’s readers would have ‘heard’ them when they read this section.

[9] Khnyok (pl. khnyokes). A pejorative term for an over-observant or holier-than-thou religious person.

[10] Bokher – A Yeshiva student or, more generally, a young man between age 13 and marriage.

[11] Hashomer Hatzair was a Socialist-Zionist youth movement in Europe, and later their affiliated party in the Yishuv in Palestine.

[12] Hebrew. The seven nations, or peoples.